Evangelo Klonis

Published Sunday, April 14, 2002

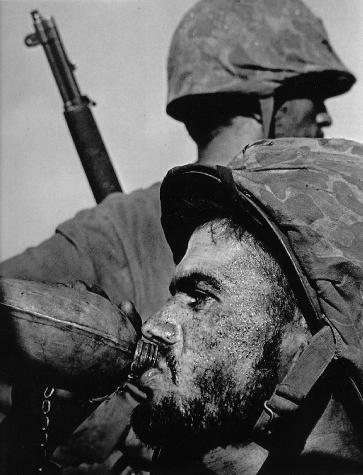

JOPLIN (AP) – The photo is so vivid you can almost taste the water coming out of the canteen. One look and you have a sense of what the cool drink must have meant to the weary soldier caught in the camera lens of Life magazine photographer W. Eugene Smith. That image of the World War II infantryman will be used on a U.S. postage stamp to be released this summer – part of a series of stamps featuring famous war photographs.

And the thirsty soldier?

He was Evangelo Klonis, the father of cardiologist Demo Klonis, whose main office is in Parsons, Kan. He also has patients in Joplin. “If my father were alive, it would have been the greatest honor to him,” Klonis said. “He was so proud to be an American, and he was so proud to have served his country.”

The elder Klonis, who died in 1989, also was featured in another famous Smith photo. In that shot, Klonis is looking off to his right, teeth tightly clenched around the cigarette in his mouth. The photo, which graces the covers of several books on World War II, has become a symbol of the actions of one of this country’s most heroic generations. And while Klonis™ face in that photograph represents an era, his life story, his son says, represents the country he loved.

Evangelo Klonis was born on the tiny Greek island of Kefallinia. One of nine children, he left his home at the age of 9 to find work and help support his struggling family. The young Klonis found a job in Athens taking tickets on a bus – a bus that would serve as his home for several years. Desperate to emigrate to the United States, Klonis would go down to the docks and watch the ships come and go. But, after taking out the money he was sending home to his family, there was little left from Klonis’s meager salary to pay for a ticket on one of the huge ships. He began casing the docks, looking for a way to smuggle his way aboard. After a while, he noticed the huge bags of coal that were loaded onto the ships. Those bags, which carried the coal that fueled the ships, would become his fathers ticket to the United States, said Demo Klonis. “He took one of those bags, dumped the coal into the water and sewed himself into the bag,” he said. He eventually was loaded onto a freighter. The elder Klonis spent seven days in that bag, his son said. “He wanted to stay hidden until the ship got past Gibraltar so it would be more difficult for the captain to turn back,” he said. After seven days, Klonis, emaciated and covered with soot, emerged from the bag and presented himself to the ships captain. With little choice, the captain allowed the boy to stay aboard and put him to work. Klonis spent a year on the ship before it reached the United States, docking just off the coast of northern California. “The captain refused to let him leave the ship, so my father jumped ship and swam to shore,” Demo Klonis said. Klonis, who spoke no English, somehow made his way south to Los Angeles and wandered the city for days listening for anyone who spoke Greek. He finally found a Greek restaurant, and from contacts made there he got his first job in a florist shop.

Like thousands of men in the Depression of the 1930s, Klonis traveled across the country in a constant search for work. He spent some time in Denver, finally settling in Santa Fe, N.M. With the outbreak of war in 1941, the U.S. government made Klonis an offer he couldn’t refuse: Any illegal immigrant who enlisted in the service would be granted U.S. citizenship. Since Klonis had received word that German soldiers had killed his family in Greece – it would not be until 1946 that he would learn that the report of his family’s death was not true – he was more than willing to sign up. “He received his citizenship papers during the Battle of the Bulge,” Demo Klonis said. Proud as he was of his service during the war, his father seldom spoke about his experiences, Demo Klonis said. “I don’t know all of the campaigns he served in, but I know he fought in North Africa, Omaha Beach and in the Battle of the Bulge,” he said.

The publicity generated by the rerelease of the Smith photos has allowed the younger Klonis to learn more about his fathers war years. “We have been getting calls from people from all across the country who say, ‘I served with your father’ or ‘My dad remembers your dad’ ” Demo Klonis said. From those calls and from the bits and pieces of information his father had shared, Klonis has gathered a more complete picture of his dad. “People call and say, ‘Did you know what your father did?’ and then they tell me great stories,” he said. Like the time Klonis’ outfit was overrun by German soldiers. “This man said, ‘We were getting our butts kicked, and your dad had had enough and climbed up on an anti-aircraft gun and turned it on the Germans.’ He told me my father saved 2,000 soldiers by doing that,” Klonis said. After the war, Evangelo Klonis returned to Santa Fe, opened a restaurant, married and raised three sons. Klonis said his fathers business career had its ups and downs, and the family split time between Santa Fe and Greece. “We were poor at times, but he always provided for us,” he said. As Demo Klonis got older, he became more aware of his father’s life and his war experiences. His father mentioned that Smith, the photographer, had traveled with his outfit and told him about the photographs. “I used to ask him, ‘Father, why didn’t you save anything from those days? and he would say, ‘I don’t need anything. I was there,’ ” he said. The family has been invited to a White House ceremony at which the stamp featuring Evangelo Klonis and others will be unveiled.